JALANE SCHMIDT: Thank you for coming. We're beginning tonight with the first night of observances of Liberation and Freedom Day here for our community, and we thought it would be important to reflect tonight on the experience of trauma, on who had the most to gain and to lose from Liberation and Freedom Day. That is, before we get to Tuesday, the beginnings of emancipation, we first have to reflect on what happened here and what happened here in our environment, where we are tonight.

DON GATHERS: And before we get too far into our program, I want to make sure that I take a special moment to offer up a thank you to each of you for coming out to attend this very special and solemn event. But I also want to take a moment to thank Elizabeth Shillue and the Beloved CVille Community for helping to organize this event and put it all together. You may see the gray T-shirts around town. So, if you see those, thank them individually, please. Please recognize that while this is a celebratory event, it is a very solemn occasion. So, please bear that in mind as we move to the different locations along this very small trek that we'll be making on this evening.

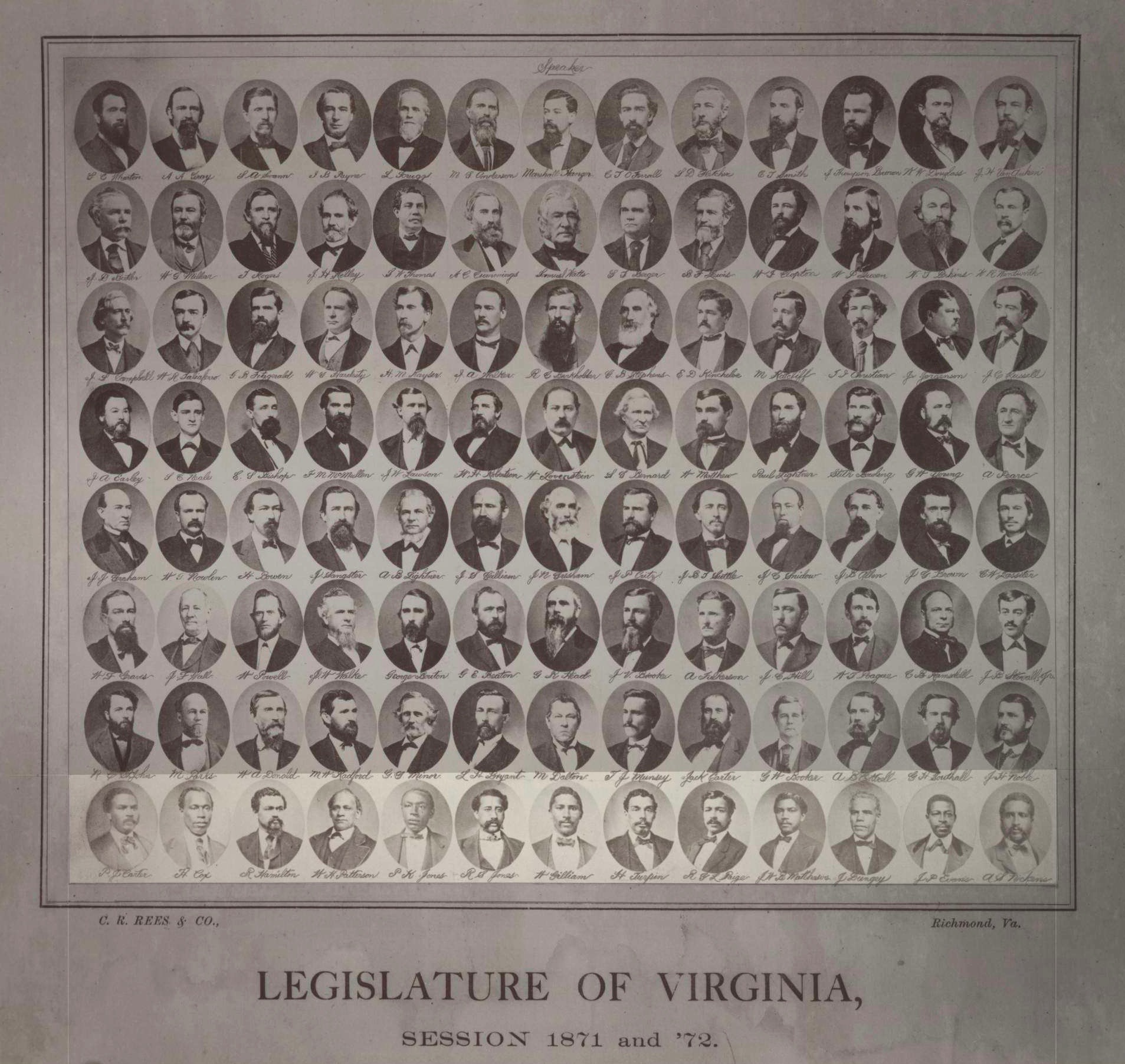

GATHERS: Why are we doing this? On this very first night of this week's observations of Liberation and Freedom Day, we are acknowledging and honoring the ancestors of our city and of our county. This solemn event is a reminder of the pain and trauma of the enslaved community who were the majority of our area residents. Tonight, we descend to the depths of pain before we celebrate on this coming Tuesday, the beginnings of emancipation. We are reckoning with history, and we're forced to reckon with that history which continues to impact our collective lives. We're gathered at the very seat of our local judicial system. This is where human beings were sold from the steps of this courthouse, then traffickers filed the papers from their transaction in the sale of those people who were considered property. This is the same justice system which today still disproportionately punishes black people

SCHMIDT: The way in which we mark and narrate our history matters to our community, especially to descendants. So, in keeping with the occasion, we want the focus to remain on ancestors and descendants. Descendants, if you desire to go to the front, if you so desire, because we're honoring their ancestors. So, we're going to walk around just this corner here of Court Square to three stations where enslaved people were bought and sold before we return here where we are now for the conclusion of our vigil. Please watch your step as we're going off and down the curb.

SCHMIDT: Our first station is at the former site of the Eagle Tavern, 300 Court Square. Right behind us, there Ms. Myra Anderson, who is a poet and activist and who is a sixth generation descendant of the Hern family of Monticello, will guide us. Ms. Myra will read aloud the names of 33 people, some of whom were her ancestors who were sold there at Eagle tavern at the Thomas Jefferson estate sale of 1829. The Reverend Carolyn Dillard, Associate Minister of Zion Hill Baptist Church of Keswick, will offer prayers for these trafficked people who were named and for their descendants. Next, we'll move to the former site of the Slave Auction Block marker, the number zero building, Zero Court Square, which is the former site of the Benson Brothers’ Auction House. There, we will hear the words, the recorded voice of Fountain Hughes, an enslaved man from Charlottesville, as he describes the pain of the buying and selling of enslaved people. The Reverend Xavier Jackson, pastor of Chapman Grove Baptist Church, will gift us with a sung meditation. Our third stop will be the Swan Tavern, right there on the corner of Park and Jefferson. There Ms. Cauline Yates, a descendant of Sally Hemings’ sister, Mary, will guide us. Ms. Cauline will read aloud the 1852 letter by Maria Perkins, an enslaved woman from Charlottesville who was being sold at this courthouse. Apostle Sarah Kelley, a Charlottesville native and pastor and founder of Faith, Hope, & Love Church of Deliverance will offer a few words and song.

GATHERS: We will come back here to the steps of the courthouse to wrap up the vigil and to offer a benediction as…we pray for our ancestors, the descendants, and each and every one of you that has taken the time out to come and gather with us on this evening. If you see someone struggling, or any of the elderly who may need help, please assist them as necessary and as you can. All right? And we will begin to proceed across the street to our first stop.

MYRA ANDERSON: In 1829, in front of Eagle Tavern, Thomas Jefferson's family sold 33 black people that the former president had enslaved. This was the largest recorded single sale of human beings in Court Square. This evening, we honor the ancestors. We say their names. Hubbard family: Abram Hubbard, Bartlett, Ben Hubbard, Betsy, Edmund Hubbard (age 16), Jerry Hubbard, John Hubbard, Jerry Jackson Hubbard (age 11), Isaiah Hubbard, Linnea, the unnamed child of Linnea (who was under two years old), Maria, Nance, Nancy, Rachel, Washington, and William Smith (age 10), all from the Hubbard family.

ANDERSON: Next family is the Gillette family: Esther Granger Gillette, Gill Gillette, James “Jimmy” Gillette, and Moses Gillette. The next family is the Hern’s family, of which I am a sixth generation descendant: Dave Hern, David Hern, Endrich Hern, Lily Hern, Ben Snowden, the husband of Lily Hern, Thurston Hern, and Stannard. And last is the Granger family: Virginia Granger and her three youngest children, who were as follows: Ben Granger (age eight), Esther Granger (age six), and Bagwell Granger (age two).

REVERAND DILLARD: Let us humble ourselves and breathe through the emotions, the pain, the truth of where we stand. Let us honor the ancestors. Let us appreciate and respect the descendants. I will be praying in my Christian faith in the name of Jesus. Father God in the name of Jesus, I come to You, Lord God, with an open heart, surrendering my will to you, Lord God, I am honored to stand on this hallowed ground. I am humbled, Lord God, to be present in this period in life, to share with the descendants as we move forward together, praying and thanking the ancestors for all they did and all they gave so that we could be free. We thank God for the descendants who have stood strong and are standing strong, arm in arm, to make a difference, to call out names, to be respected, to have their voices heard. I thank you for this community, Lord God, that prayerfully and, not just words but in language and in movement, that we move forward, not in a stagnant way, Lord God, but that we move together in true unity where the truth of the Black Spirit, the truth of the African American is known as equal. Lord God, we thank you. In addition, Lord God, I would be remiss if I did not ask for prayer for the oppressor, Lord God, touch their minds. Touch their hearts. Open their minds. Lord God, that superiority will not be the language of the day, but that common purpose and common love and unity do. Dedication to life and respect is what we all will move forward in together. In the name of Jesus, amen.

(CROWD: Amen.)

FOUNTAIN HUGHES: My name is Fountain Hughes. I was born in Charlottesville, Virginia. My grandfather belonged to Thomas Jefferson. My grandfather was a hundred and fifteen years old when he died. And now I am one hundred and one year old. Now, in my boy days we were slaves. We belonged to people. They’d sell us like they sell horses and cows and hogs and all like that. Have an auction bench, and they’d put you on…up on the bench and bid on you just same as you bidding on cattle, you know. But still, I didn’t like to talk about it. Because it makes, makes people feel bad you know.

(Piano interlude)

REVEREND JACKSON (SUNG): Though the storms keep on raging in my life, and sometimes it's hard to tell the night from day. Still, there's hope that lies within, gets reassured. As I keep my eyes upon the distant shore, I know He'll lead me to that blessed place He has prepared. But if the soul don't cease, and if the winds keep on blowing In my life, my soul has been anchored in, in the Lord. Though the storms keep on raging in my life, and sometimes it's hard to tell my night from day. Still, there's hope that lies within. It gets reassured as I keep my eyes upon the distant shore, I know He'll lead me safely to that blessed place He has prepared. But if the storms don't cease, and if the winds keep on blowing in my life, my soul, my soul has been anchored in, in the Lord.

REVEREND JACKSON (SUNG): Oh, I realize that sometimes in this life, you're going to be tossed by the waves and the currents. They seem so fierce, but in the Word of God, I've got an anchor, and it keeps me steadfast and unmovable despite the tide. And if the storms, if they just won't cease, and if the wind keeps on blowing in my life, my soul, my soul's been anchored in, in the Lord. My soul's been anchored, my soul's been anchored, my soul's been anchored, my soul. For the bills may roll, the breakers may dash, I shall not sway, because he holds me fast. So dark the day, clouds in the sky, but I know it's alright, cause my Jesus is nigh. My soul has been anchored in the Lord.

(Applause)

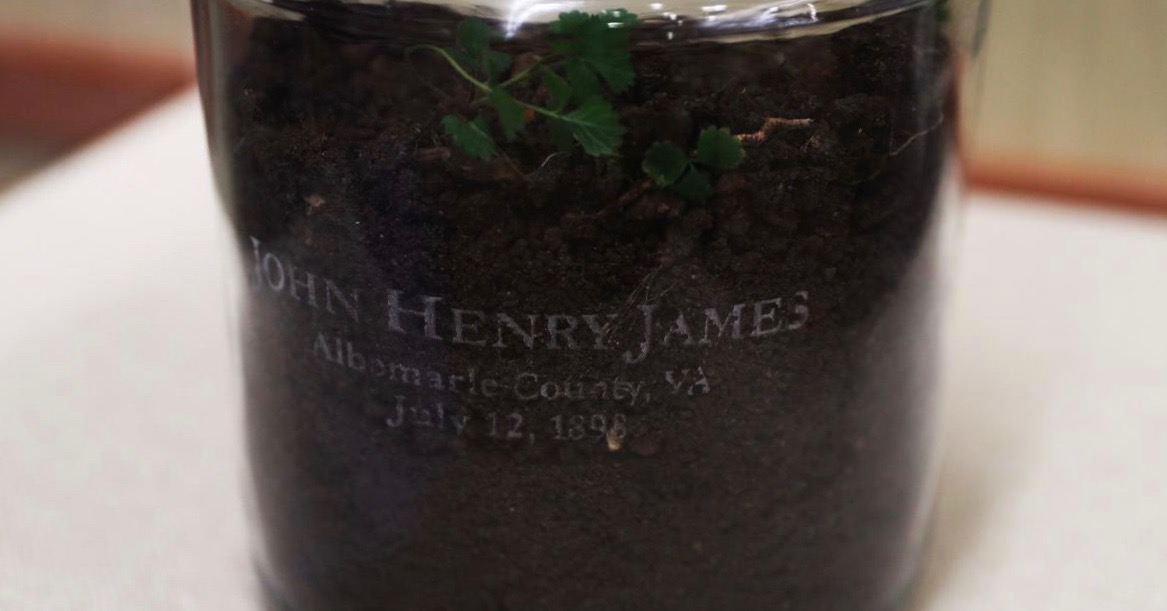

CAULINE YATES: My name is Cauline Yates. In 1852, just four days into the October term of the Albemarle County Court, Maria Perkins, an enslaved woman in Charlottesville, wrote this desperate letter to her husband, Richard: “Dear husband, I write you a letter to let you know of my distress. My master has sold Albert to a trader on Monday court day and myself and other child is for sale also. I want to hear from you soon before next court if you can, I want you to tell Dr Hamilton or your master if either will buy me they can attend to it now. Don't wait a trader to get me. I don't want a trader to get me. They took me to the courthouse. A man by the name of Brady bought Albert and is gone. I don't know where. They say he lives in Scottsville. I'm so heartsick and I am ever will be your kind wife, Maria Perkins.” (Full transcript as written)

APOSTLE KELLEY: Even listening as that letter was read and thinking about how our family was so scattered… I had said I didn't mind, but I'm realizing it's affecting me. But I could just hear them, and the song that came to my mind.

ASPOSTLE KELLEY (SUNG): No more weeping or wailing, no more weeping or wailing. There'll be no more weeping or wailing, because we are going to be with God. Soon we'll be done with the troubles of this world, the troubles of this world, the troubles of this world. Oh, soon, we'll be done with the troubles of this world, going home to be with God. There'll be no more weeping or wailing, there'll be no more weeping or wailing. There'll be no more weeping or wailing because we're going to be, ‘cause we're going to be, ‘cause we're going to be with God.

GATHERS: Everybody, please come on in and gather closely. As we move towards the conclusion of our program…What we have scheduled now, I will indeed ask that the descendants will lead us in this specific portion. My dear Sister, Reverend Brenda Brown-Grooms, will lead us as only she can, in song. And as we're doing so, I would ask that all who are, who are present, available, and capable to come and pour out a libation to our ancestors and to and to those who have gone on before us and whose shoulders we stand on today. So as she leads us in song, if those who can, will come, just dip into the basin and pour out into the ground, libation. Thank you.

REVEREND BROWN-GROOMS: I come back to this song time and again. It was the first thing I could sing after my stroke, which left me paralyzed on my right side, head to toe, including my right side of vocal cords. But this song came back first of all. It's important, because it speaks of people who lost their names into slavery and who gained a faith in the God whom we knew before we came to these shores. And we said it with these words that even if you take everything for me, I believe you'll allow me to live. “I Told Jesus.”

REVEREND BROWN-GROOMS (SUNG): I told Jesus, it would be all right if he changed my name. I told Jesus, it would be all right if he changed my name. I told Jesus, it would be all right if he changed my name. Be alright, yeah, be alright if he changed my name. He say, your Mama won't know you, child. Your Papa won’t know you, too. Be all right, yeah, be all right, if you change my name. I told Jesus, it would be all right if he changed my name. I told Jesus, it would be all right if he changed my name. I told Jesus, it would be all right if he changed my name. I told Jesus, it would be all right if he changed my name. Be alright, yeah, be alright if he changed my name.

GATHERS: Please continue to come forward, anyone who wants to participate.

CROWD (SUNG): Wade in the water, wade in the water, children, wade in the water, God is gonna trouble the waters. Wade in the water, wade in the water, children, wade in the water, God is gonna trouble the waters.

REVEREND BROWN-GROOMS (SUNG): See that band all dressed in white,

CROWD (SUNG): God is gonna trouble these waters,

REVEREND BROWN-GROOMS (SUNG): Well, It look like a band of Israelites,

CROWD (SUNG): God is gonna trouble these waters. Wade in the water, wade in the water, children, wade in the water, God is gonna trouble the waters. Wade in the water, wade in the water, children, wade in the water, God is gonna trouble the waters. Oh, God’s gonna trouble the water, God’s gonna trouble the waters, God’s gonna trouble the waters.

GATHERS. God bless you. Are there others? If so moved, please come forward.

GATHERS: I pray that as you stand with me, you'll recognize that while this was very much ceremonial, it was extremely powerful and very much appropriate and necessary for this gathering and for this moment. This is a ritual that goes back well… into our deep, into the depths of our ancestry. And I'm just happy that so many people decided to participate in it on this evening. As we move forward towards the conclusion of this…program and this event, as we move towards our benediction, I would like for Ghislaine and Elizabeth to come forward as well. And please, continue to come and participate in the libation ceremony. Again, I just want to recognize these two young ladies did so very much work on putting this together, and being able to come out and get this type of gathering and this type of response is truly incredible. And I really would like to give both of them a round of applause at this moment.

(Applause)

GATHERS: As we move towards…our dismissal, excuse me.. let us bow and go to the throne of Grace. Father, it is indeed in your immense wisdom that we were gathered here today and we thank you for this event, dear Lord. We thank you for every head, heart, mind and soul that's gathered here. We thank you, dear Lord, for those who wanted to be here before whatever reason could not. We thank you for our visitors from out of town who have come. We thank you for moving on the hearts of each and every man and woman here today, dear Lord. Father, we as we stand here upon the shoulders of our ancestors, we recognize, dear Lord, that all that they were able to do was indeed through and by You. And Lord, we just love you and we uplift you because of that. We exalt you, dear Lord, we shout hallelujah for all that we have seen and all that we've overcome, knowing that there is still full measures that we need to achieve. We stand with you, dear Lord, knowing that you will never forsake us and never leave us. And we thank you, dear Lord, for being with us thus far along this journey. Father, as we leave this place, but never from your presence, dear Lord, we pray for traveling mercy as we separate to our several homes. We pray that you will indeed dispatch your angels in mercy and of goodness, dear Lord, to be upon each and every individual, and pray for a safe arrival, safe travel, safe passage. Lord, we love you, we honor you, we praise you, and we uplift your name as well as the descendants and the ancestors. And we offer this prayer unto you in, Jesu’. Precious Name. Amen.

(CROWD: Amen.)

GATHERS: I thank each and everyone for coming. Unless there's anything on anyone else's heart on this evening that concludes our program. Thank you.